34: Litija // The Geometric Centre of Slovenia

Smack bang in the middle of the country // © John Bills

While it may be somewhat unconventional, it is exactly the sort of thing that appeals to me as a tourist attraction. There is disappointment at the heart of it, life usually hints in that direction, but there was something about ‘the geometric centre of Slovenia’ that was always going to stir a little joy in me. I always loved the idea of straddling Europe and Asia in the Urals, of setting foot in either the great north or the deep south. Heck, I even like the idea of a day in Llanymynech, where the main road divides the town between Wales and England. Geography-centric tourism is a winner for me.

The geometric centre of Slovenia lies in a tiny hamlet called Spodnja Slivna, just a short drive from a village called Vače, itself famous for being the birthplace of Matija Hvale, Slovenia’s first philosopher and first printed author. Pleasant enough, Vače existed in my experience as the place from which we’d head off to the GEOSS monument, the Geometrično središče Slovenije, a co-ordinate heavy obelisk surrounded by a variety of other monuments paying homage to the history of these people.

Monuments such as the GEOSS can only ever be emotionally underwhelming. The monument itself was a charming piece of work, but the excitement that builds with the idea of geography-based adventuring can only breed disappointment. No, disappointment is too strong a word, but the point stands. The expectation is that when faced with this point of topographical interest, something will change, but nothing does. You are simply the same person you were before, only now you are looking at something interesting. Geography-centric tourism is a winner for me, but the win is eternally muted.

Vače wasn’t all about the monument. Despite a population that dipped below 300, the village was charming in all of the ways that Slovenian villages tend to be. The Church of St Andrew provided an ecclesiastical fulcrum that was home to one of the most impressive tombs in the country, a shimmering 19th-century piece that came out of the famous glassworks in Ostrava (modern-day Czechia), itself accentuated by soil kissed by none other than Pope John Paul II.

We continued to skirt around Litija in search of curiosities, passing through hills that were every bit as rolling as you’d expect undulation to provide. The hills were dotted with smoking piles of some unclear black material, material that turned out to be charcoal. A dying art that somehow survives in the hills around Litija, carbonised wood is burnt to create excellent charcoal, although it was the aesthetic qualities of the tradition that interested me most. The piles looked delightfully akin to those other piles, the ones that gave Dr Ellie Sattler so much excitement in a famous 1993 movies. I resisted the temptation to plunge my arm into the burning charcoal in search of West Indian Lilac, a resistance that I have since come to regret.

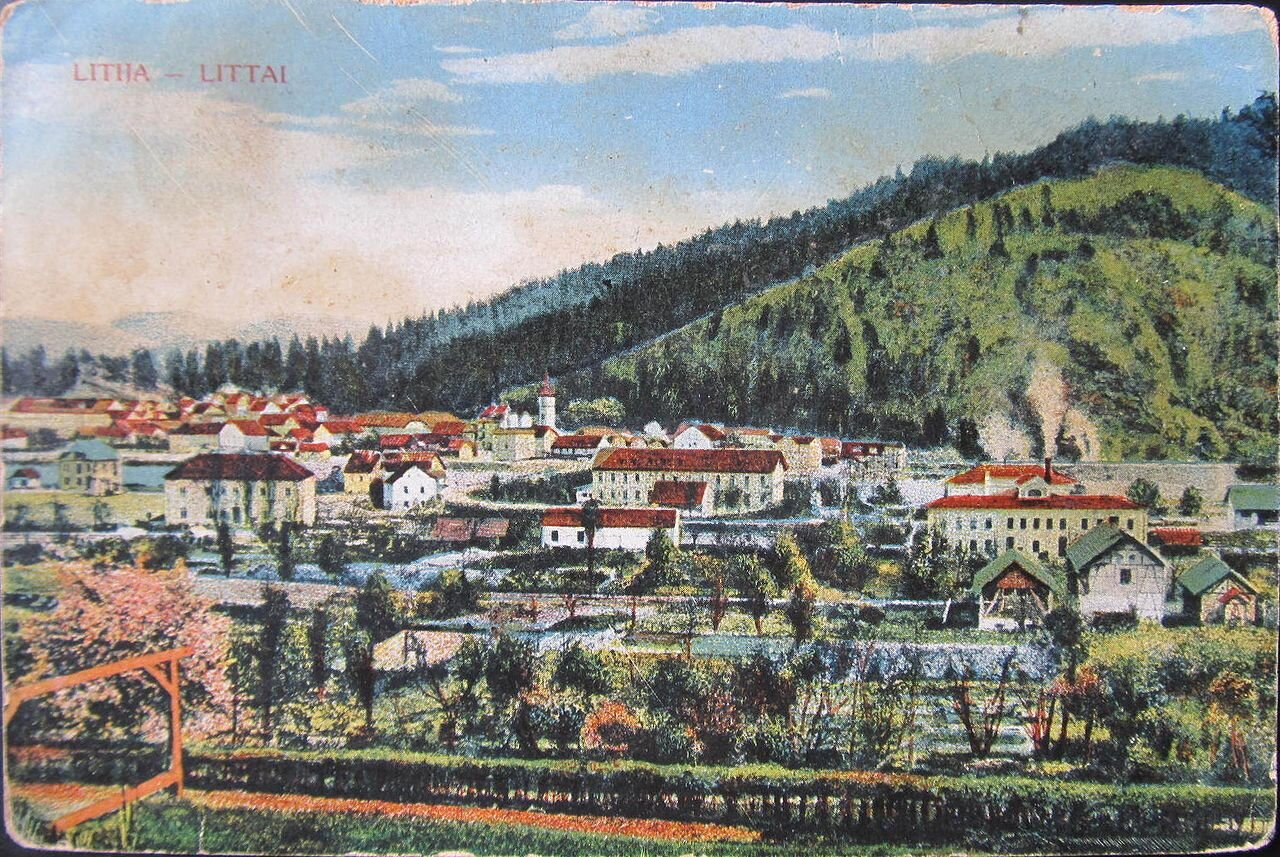

Eventually, our tour made it to Litija itself, where I sauntered around in search of curiosity. Instead, I found composition, namely a museum dedicated to one of the greatest composers of the 20th century. What the heck did Carlos Kleiber have to do with a little town in the very heart of Slovenia? Maybe nothing, maybe everything, maybe both, maybe all three, but it didn’t take long for me to enter the museum in search of answers. Long story short? The man from Berlin married a young Slovenian ballet dancer called Stanislava Brezovar, herself famous for starring in a seven and a half-hour ballet epic called Ples čarovnic. The two are buried not too far from Litija, so a museum dedicated to the fragile power of Kleiber’s compositions made a whole heap of sense. The museum tour continued with the Museum of Litija, a three-exhibition showcase for the history and culture of the town, with much attention paid to industry, and the only river traffic collection in the country taking centerstage. This was once an industrial hub, after all, Litija’s Sava shipyards bringing prosperity that has long been committed to nostalgia.

And that was it, nostalgia and geography conspiring to bring my day to an end. Did I learn much about Litija? Yes and no, although whenever that is the answer you can guarantee that the truth lies somewhere between the two. Does it matter? That is a much more robust ‘no’, as a commitment to learning something about everything at all times will only lead to a tired mind of crossed wires and confusion. I came to Litija, I saw Litija, I registered Litija, but my intrigue didn’t stretch beyond that and the fault lies with me, although there really is no fault at all there. Bucket list items aren’t all about skydiving after all, and I could finally say that I had stood on the geometric centre of Slovenia.