30: Idrija // Mercury and Lace, Obviously

An aerial shot of Gewerkenegg Castle in Idrija, Slovenia // © Iakov Filimonov / shutterstock

I’m not going to get into a discussion about what the very best museum in Slovenia is. The whole argument is subjective, surely? It all depends on what you want your museums to look like, what you want them to contain. The general consensus will direct brains towards art and culture, naturally, but give me a Railway Museum and I’ll be as excited as the proverbial pig in shit. Not that I know anything about how pigs feel about faeces, none of us does, and don’t try to tell me otherwise. All I can say is that I absolutely love railway museums.

This is veering off track, as such things usually do, so I shall bring the focus back to the museum question. The very best museum in Slovenia? I can’t answer that, but I can guarantee a few names that must be in the discussion. The Posavje Museum in Brežice has received its kudos, while the Božidar Jakac Gallery in Kostanjevica na Krki demands attention. KSEVT in Vitanje too, that place is out of this world. Of course, Ljubljana is home to plenty of excellent museums, including the aforementioned Railway Museum.

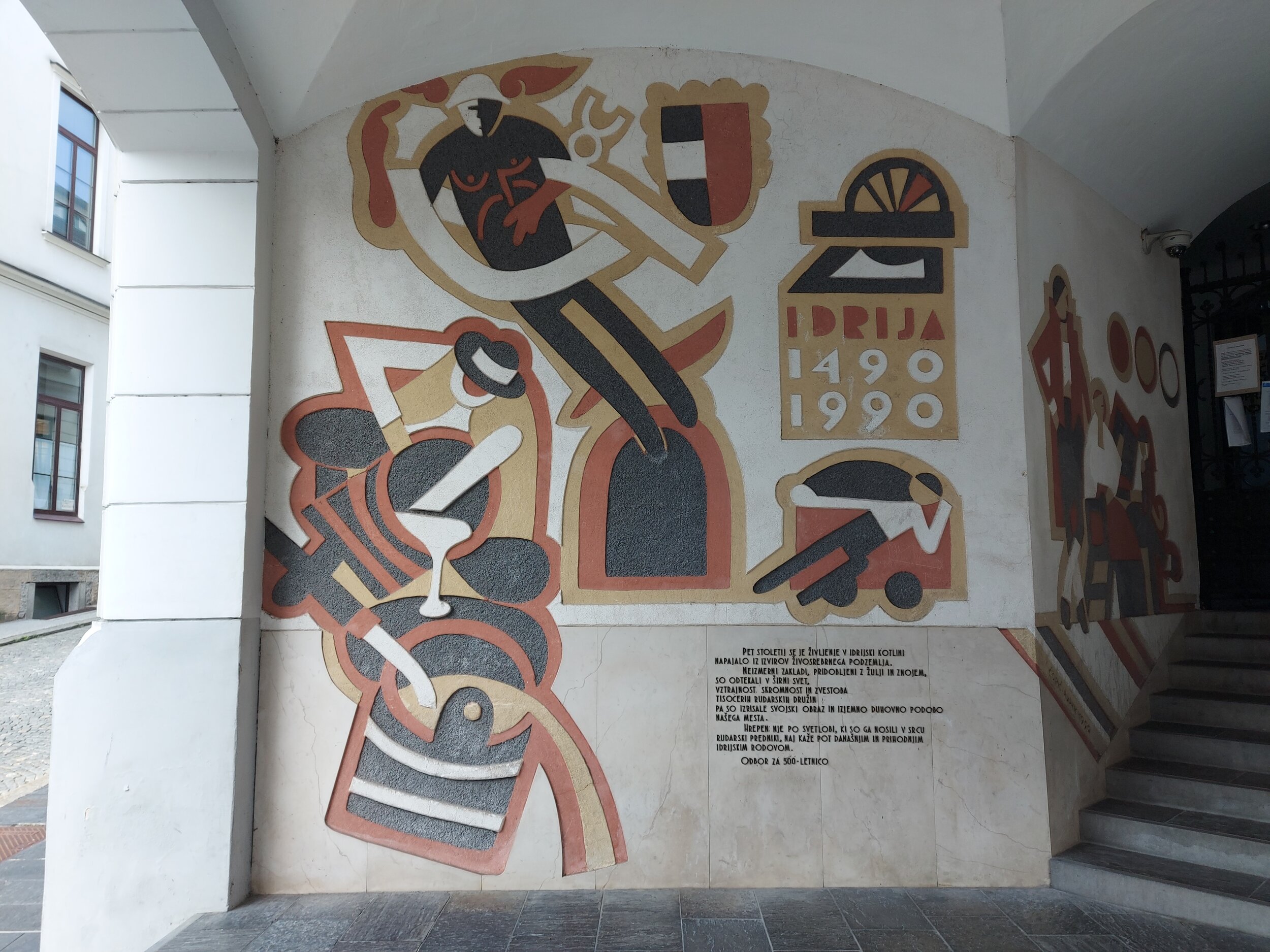

Any such discussion will focus plenty of attention on the Idrija Municipal Museum, located within the towering walls of Gewerkenegg Castle in the heart of a town as famous for mercury as it is for lace, two true polar opposites. This is an award-winning museum, a fact as plain as the blue sky to anyone who has been here, such is the breadth and depth of the exhibits and information on view.

Before getting to that museum I had to navigate a simple bus journey through many towns that I’d put in the usual suspect pile, places like Cankar’s Vrhnika and, erm, Gosar’s Logatec? It matters not. The only real thing of note was a pub called Turk in the village of Hotedršica, a name that took me by surprise until I learned that it was a family name and not something to do with the Ottomans. Make of that, what you will.

Anyway, Idrija, a small town of fewer than 6,000 people that has marked history more than most towns of that same size. That history is lovingly displayed in the many rooms of the castle, and attempting to go through it all here would be an exercise in futility. You’ve got modern art, an in-depth look at life under Italian and German occupation, a detailed exploration of Communist Idrija, and more mercury and lace than one could ever dream of.

They really are a combo, aren’t they? Mercury and lace go together like, well, mercury and lace. The former is just about as dangerous as liquid elements get, although that hasn’t always been the presumption. Those in the know in Ancient China and Tibet thought that mercury use could help prolong lives, although there is a quaint irony in the first emperor of a unified China (buried in a tomb filled with mercury, no less) dying after drinking it in the hope of gaining eternal life.

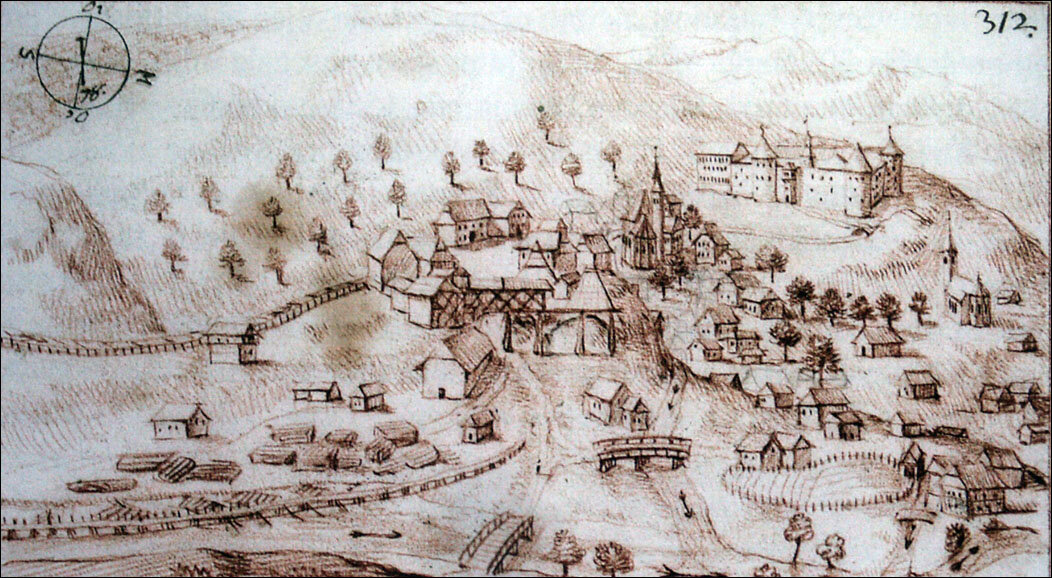

Drinking mercury (chemical symbol Hg, for the record) is idiotic behaviour, but the discovery of quicksilver was key to Idrija’s early development, and thus the fortunes of the town became dangerously allied to men being exposed to the stuff. It all began in the late 15th century when a simple tub worker found a weirdly heavy silver liquid in one such tub, and the rest is history. Idrija became the mercury centre of the globe, supplying the entire world with valuable liquid and becoming the first Slovenian mining town in the process.

With mining came jobs, and with jobs comes a population boom. Idrija grew and grew with the overwhelming majority of its people working in the mining business, which was about as good for the physical health of the town as you’d imagine. So, while the men were sweating away underground, excavating a substance that did immeasurable harm to their health, what were the women of Idrija up to?

Okay, it is far too easy to divide Idrija between blokes dying in mercury mines and women patiently making beautifully fragile lace, but it isn’t a million miles away from the reality of it all. That’s just how it was. Does it paint a somewhat sexist picture of the past? Sure, but facts are facts.

Besides, there should be no complaints, because nobody died from working with Idrija lace. Quite the opposite in fact, as the delicately interwoven threads of handmade Idrija lace have given joy to people all over the world for years. The town is home to the oldest lacemaking school in the world no less, ensuring that this trademark piece of beauty will continue for years to come. Inside the Municipal Museum was an exhibition titled ‘Idrija: A History Written In Thread’, and that pretty much sums it up.

Dividing Idrija between violent mercury and alluring lace is easy, but it is almost a disservice to this quaint little town in the west of the country to focus solely on those opposing creations. After exhausting my brain in the tremendous museum I was in need of sustenance, and that came in the form of žlikrofi, filled-dumplings of a kind that became Slovenia’s first protected dish, way back in 2010. Throw in a darling town centre and you’ve got yourself one heck of a town.

All the while, I couldn’t quite work out just why the castle had such a silly name. What the heck is a Gewekenegg, anyway? Sounds like a breakfast cereal to me. The answer probably lay in the museum, but it was crushed under the weight of mercury, lace, dumplings, history, modern art and more dumplings.